Processing the records of the New York Zoological Society’s (now the Wildlife Conservation Society) Center for Field Biology and Conservation (CFBC) was like a crash course in the Society’s field research and wildlife conservation efforts of the 1970s. In this post, I’ll give you a glimpse of both the CFBC’s history, as seen through its records, and the processing process itself. (Archival terms are linked to the Society of American Archivists glossary.)

Processing the records of the New York Zoological Society’s (now the Wildlife Conservation Society) Center for Field Biology and Conservation (CFBC) was like a crash course in the Society’s field research and wildlife conservation efforts of the 1970s. In this post, I’ll give you a glimpse of both the CFBC’s history, as seen through its records, and the processing process itself. (Archival terms are linked to the Society of American Archivists glossary.)

Generally, the first thing a processing archivist does when starting work on a collection is research the history of the creator to provide context to the records. This information will eventually become a part of the finding aid, which is what archivists call the document that summarizes a collection’s contents. Using William Bridges’s Gathering of Animals and reference materials put together by the WCS Library and Archives, I discovered the Center’s place in NYZS history. While it only existed under that name for seven years (from 1972 to 1979), the Center and its researchers conducted groundbreaking research in numerous locales and with multiple species. Prior to 1972, these researchers had worked under the Institute for Research on Animal Behavior, a joint venture with Rockefeller University. In 1979, the Center was merged with the Department of Conservation, and the resulting department was named the Animal Research and Conservation Center. (Since then, it has become a full-fledged division and been renamed three more times.) The reorganizations in 1972 and 1979 changed the administration of the research programs from New York, but did little to change the experience of researchers in the field. In fact, this collection contains records from as early as 1969 and as late as 1982, spanning three iterations of the department.

For more on the Center, you can download this 1972 Animal Kingdom article, found in the collection.

After I understood the context in which the records were created, I took a look at the records themselves. When possible, archivists attempt to maintain the original order of collections. In this case, while the folders themselves were labeled, any order among the folders had long since been lost. Therefore, it fell to me to determine how to arrange the collection into series. Because the collection contained the records of three main researchers (George Schaller, Roger Payne, and Thomas Struhsaker), I decided to create a series (a subdivision of the collection) for each of them. This made sense based on both archival principles – keeping records produced by each creator together – and ease of use, as researchers are likely to be interested in all records by a creator. I created a fourth series (“general administration”) for records that did not pertain to one researcher in particular, and broke each series into subseries based on record type (e.g. correspondence, financial records, and writings). As I went through each file to determine where to put it and what to label it, I also removed material with individuals’ checking account numbers, made notes what files had to be restricted (generally due to including a researcher’s social security number), and performed basic preservation measures. These include removing paper clips (which can rust and stain paper), putting everything into new, acid-free folders, and placing acid-free paper around newsprint and other yellowing paper.

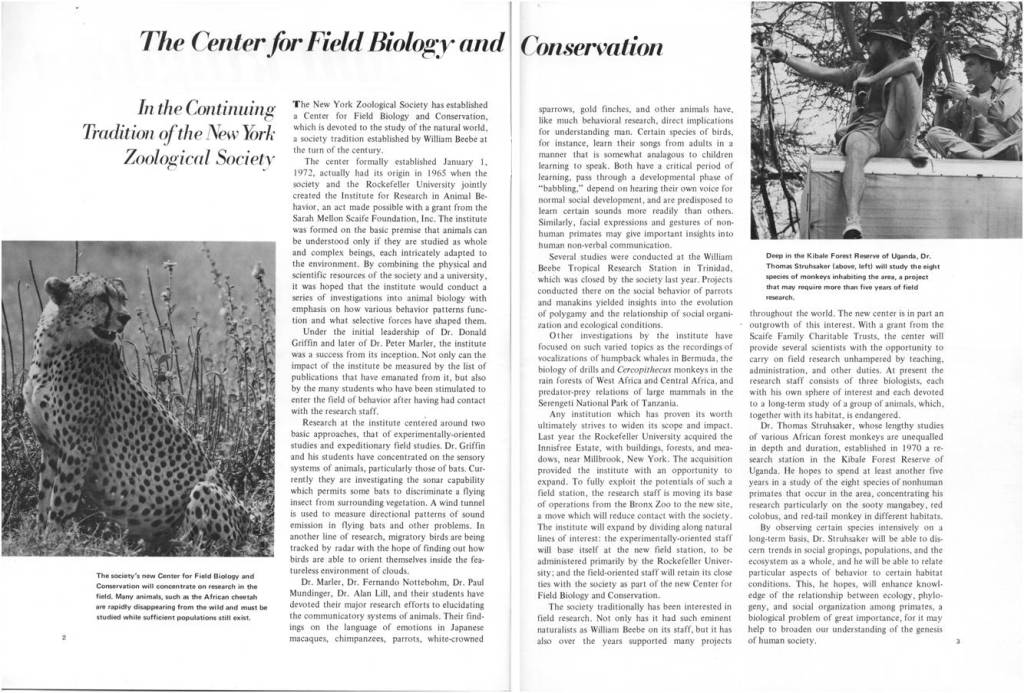

While the collection mostly contains textual documents, there are also a few physical objects, such as these vehicle log books and this collection of whale song recorded by Dr. Roger Payne and published by National Geographic.

When the physical arrangement was complete, it was time to describe the collection in a way that researchers could find and use. The WCS Archives uses a special Excel spreadsheet. After an archivist enters the folder list into the spreadsheet, it uses formulas to produce the list in EAD, a markup standard used by archivists. (For more on EAD, see here.) From there we import the list into a program called Archivists’ Toolkit, where we can add the rest of the description. It is then exported again and uploaded to the Archives’ LibGuides site. And thus, the finding aid for the collection was born, and the records are ready to be discovered by users.

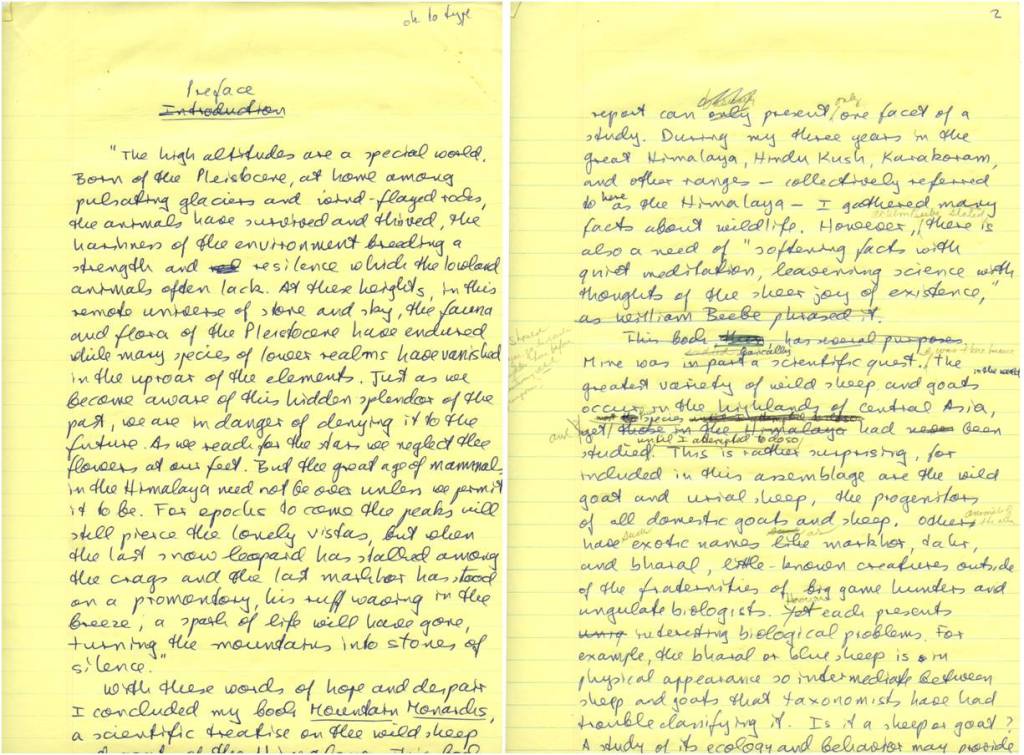

One of the chief pleasures of archival work is seeing documents written in the creators’ own hand. Here, a handwritten draft of a book on snow leopards by Dr. George Schaller.

One of the most interesting things about this collection to me is how it shows how the various research projects were funded. Each researcher’s series contains both funding and financial records subseries. The former shows how the researchers applied for grants, and what grants were awarded. The latter shows how the money was spent. Together, they show what was researched and how, as well as the importance of grant funding for this type of work. Below, you can see the cover page for one of Dr. Thomas Struhsaker’s grant applications, along with the approval letter.

This and other behind-the-scenes stories of the Center for Field Biology and Conservation can be found in the WCS Archives. And for more on conservation at the New York Zoological Society, check out former intern Alexanne Brown’s post on the International Conservation bluebooks.

This post is by Helen Schubert Fields, who worked during Fall 2014 with the WCS Archives as an intern processing the records of the Center for Field Biology and Conservation. All items pictured are from that collection: New York Zoological Society. Center for Field Biology and Conservation records, 1962-1982 (bulk 1969-1979). Collection 4062.