The generations of zoogoers visiting the World of Birds will either insure the survival of wildlife through interest and concern, or its destruction through negligence and exploitation.”

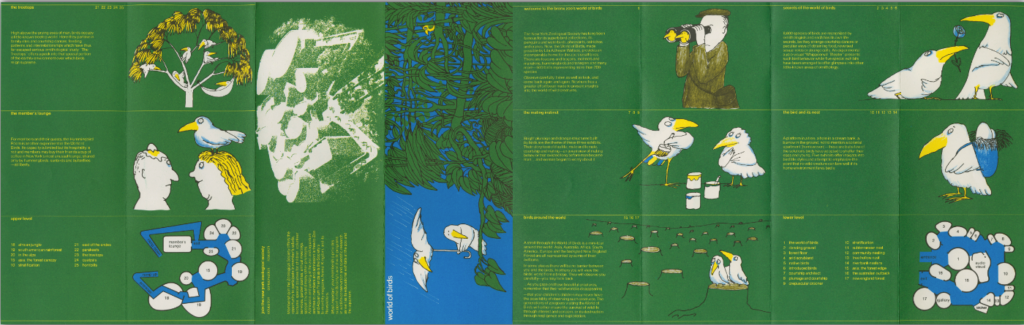

World of Birds pamphlet, 1972

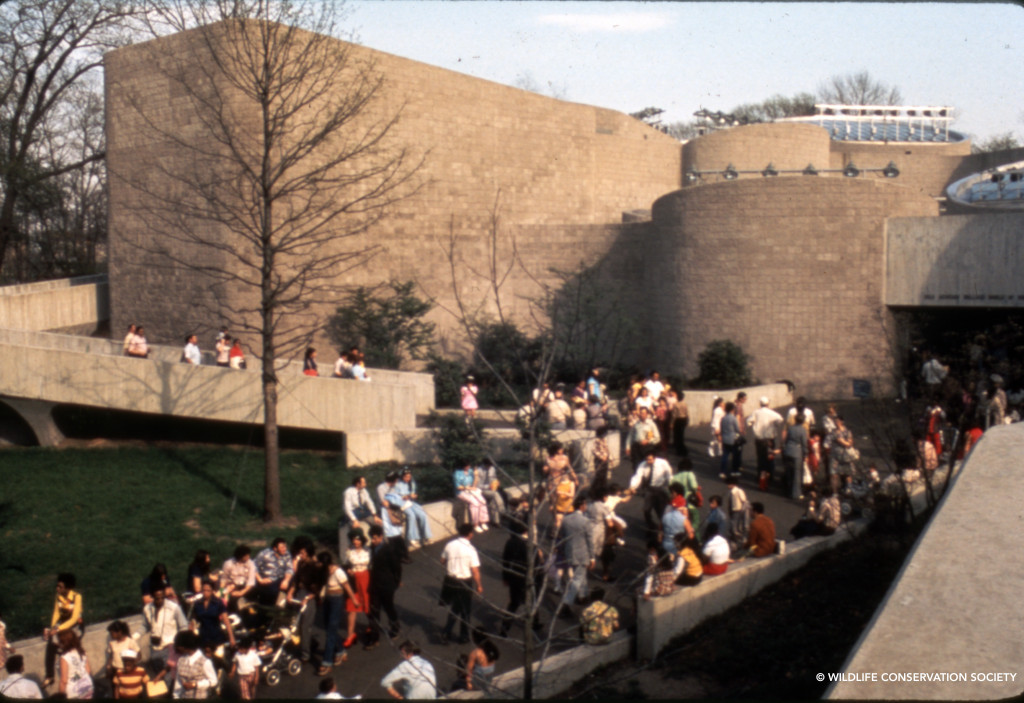

The World of Birds opened on June 16, 1972. The gift of Lila Acheson Wallace, for whom the building is named, it was widely considered among the most innovative zoo exhibits upon its opening, and it continues to be a Bronx Zoo icon.

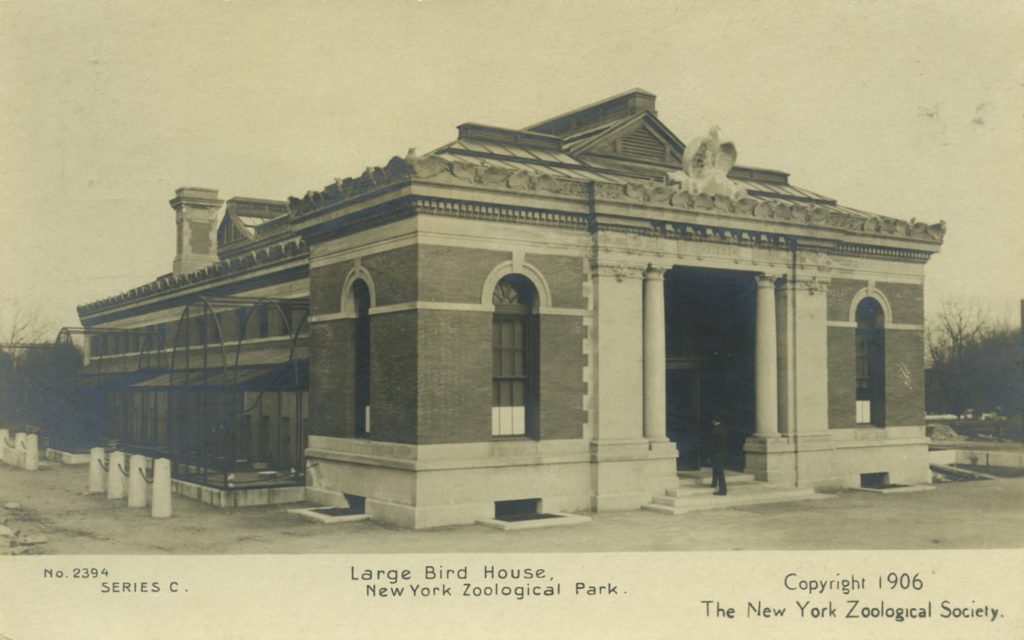

The first Bronx Zoo Bird House opened in 1905 under the direction of the zoo’s first Curator of Birds, William Beebe. Its design was an attempt to deliver on early WCS leaders’ intentions to create a zoo that would be a “decided advance beyond anything thus far accomplished.” Although many of the Bird House’s features—including live plants and multi-species exhibits—were considered radical at the time of its opening, the evolution in zoo design over the course of the twentieth century led to WCS’s view by the late 1950s that the Bird House was outdated and sparked plans for the modern exhibit that would become the World of Birds.

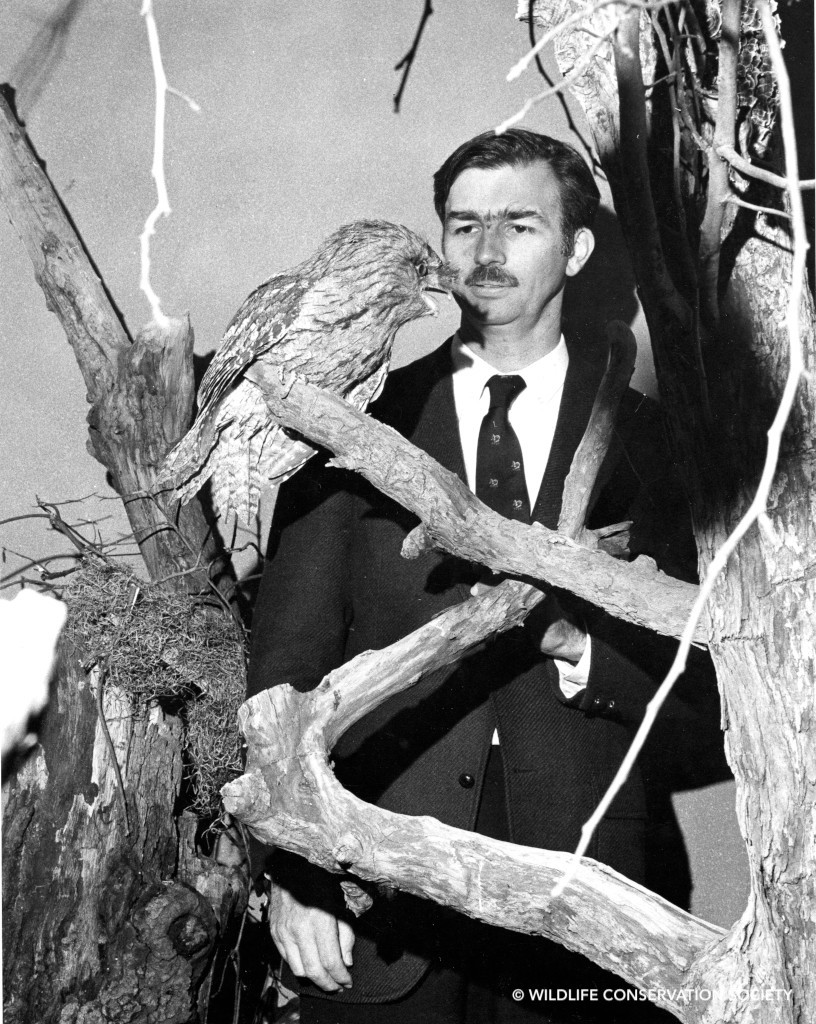

William Conway developed the concept for the World of Birds. At that time NYZS General Director, Bronx Zoo Director, and Ornithology Curator, Conway also oversaw the project’s planning, development, and construction.

Composed of a series of large interconnected cylinders with skylight roofs, and sweeping exterior ramps, the World of Birds was planned for the exhibition of 500 birds representing more than 200 species and subspecies in 25 separate exhibit areas. The building’s lead architect, Morris Ketchum Jr., said of the design in the New York Times, “We didn’t worry about how the place looks from the outside. Conway’s very much against spending effort and money on exteriors except where it does something for the animals, but don’t think it’s any the worse for that. What we did was simply build the exhibits, or habitats, as well as we could, then put a protective skin around them. It’s striking just as it is.”

The architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable was among the many who were indeed struck by the building’s Brutalist design. She admiringly described its form in a New York Times review as an “asparagus-like bunch of cut-off cylinders, ellipses and free forms joined by ramps.” The World of Birds, Huxtable wrote, “is surefire drama and painless education. And fun.” She welcomed the new building as a sign of an always evolving institution, declaring that “There are no flies on New York’s Bronx Zoo. It entertains, instructs and proselytizes, and it uses the tool of architecture to do so with singular skill.”

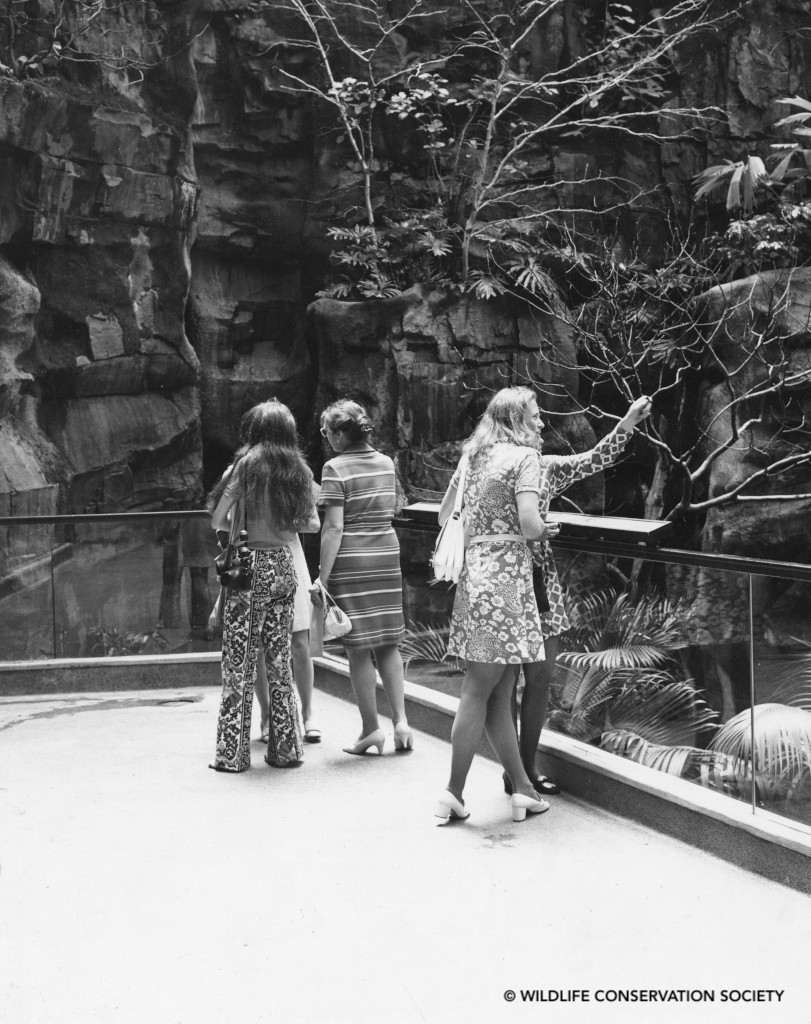

Aside from the building’s exterior, several features contributed to building’s ingenuity. Although the World of Birds was often noted for its barrierless displays, these had been used before, in St. Louis and Philadelphia for instance. They had been used as well in the 1964 Bronx Zoo Aquatic Birds House, also led by Conway, which served as a testing ground for concepts that would make World of Birds so innovative. What was new about the World of Birds was the development of immersive displays, like the African Jungle and South American Rain Forest exhibits, that placed visitors inside the exhibits. The displays were enhanced by advanced features and exhibit technologies. Among these were a 120-foot-long, 50-foot-high fiberglass cliff (based on a mold of the New Jersey Palisades); a 40-foot waterfall; natural plants and live trees as well as fiberglass and cork trees; multi-level displays; built-in watering systems; artificial rainstorms including mists, sounds, and strobe lights; backgrounds utilizing new airbrushing techniques; and film displays to supplement graphics.

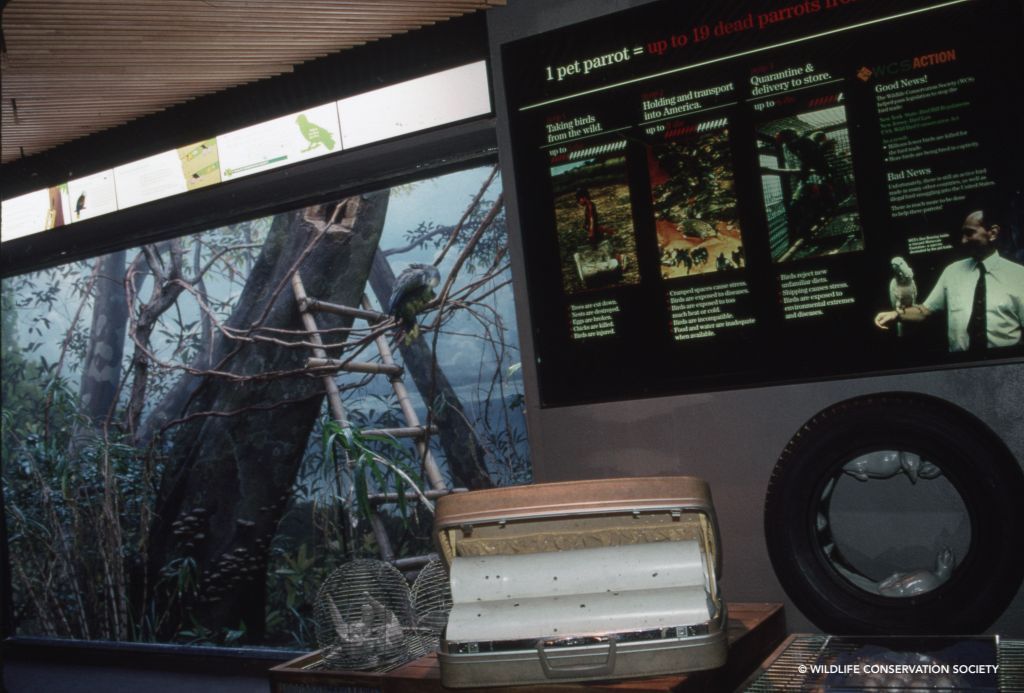

The World of Birds was designed to “awaken concern for the natural world,” and from the start, the building’s signage included messaging about threats to birds and their habitats. An introductory pamphlet about the building included an appeal to visitors: “As you gaze on these beautiful creatures, remember that their wild world is disappearing—that your children’s children may never have the possibility of observing such creatures. The generations of zoogoers visiting the World of Birds will either insure the survival of wildlife through interest and concern, or its destruction through negligence and exploitation.”

Indeed, WCS believed strongly in the building’s ability to inspire visitors to take conservation actions, explaining elsewhere that “An enormous effort has been made to carry into the city some suggestion of the beauty of the natural world in which birds dwell outside. It seems likely that the vast majority of visitors to the World of Birds and their children after them will have little opportunity to see wild animals in nature. Nevertheless, it will be this growing municipal population whose feeling toward wildlife, reflected in their votes, will ultimately shape the future of national parks and wildlife refuges and the opportunities future generations will have to see and enjoy wildlife. That is what the World of Birds is all about.”