“Without documents; no history. Without history; no memory.”

– Mary Ritter Beard (Historian, archivist, author and member of the Society of Women Geographers, quoted by Jayne Zanglein in The Girl Explorers [2021], 165.)

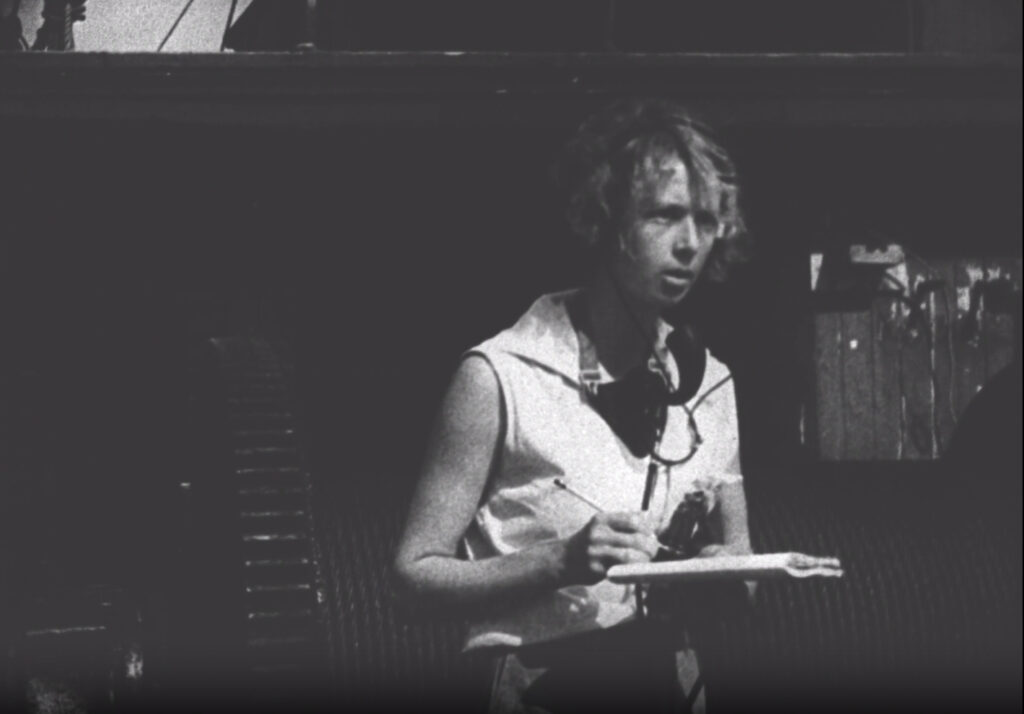

As the Project Assistant for the WCS Library and Archives’ Recording at Risk project, funded by the Council of Library and Information Resources (CLIR), one of the most rewarding experiences of digitizing the Department of Tropical Research Film Collection was unearthing films made by carcinologist Jocelyn Crane and ichthyologist Gloria Hollister. The Department of Tropical Research (DTR) was rare in employing both men and women field scientists in the 1920s through the 1960s. In addition to being excluded from conducting research in laboratories, women scientists were thought by some to be too socially distracting to travel and work alongside men abroad.

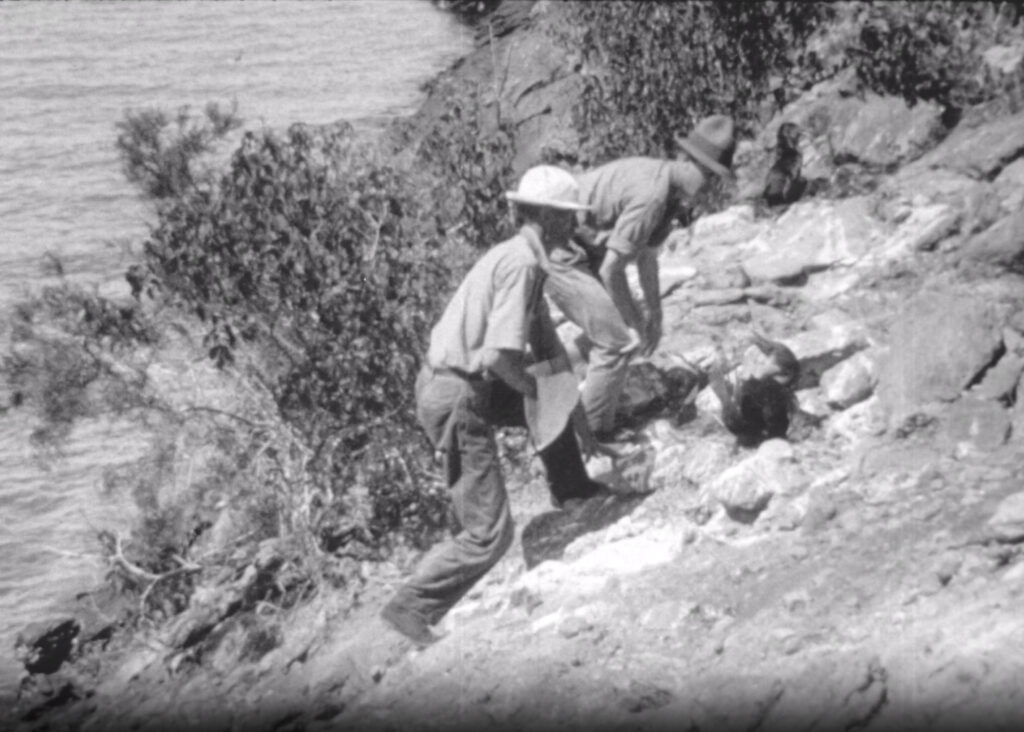

The above reel is the earliest footage WCS has of Gloria Hollister, who joined the DTR in 1929 as a marine biologist specializing in the study of fish. During her time in Bermuda Hollister developed a new technique for preparing fish specimens in which the skin and internal organs of the fish were made transparent, allowing the skeletons of fish to be visible for study without dissection. The first part of the reel shows her communicating through phone wire with DTR Director William Beebe during his deep-sea dives in the Bathysphere. In the 1930s, Hollister made several historic dives in the Bathysphere, reaching a depth of 1,208 feet in 1934. She held this record for the farthest underwater descent made by a woman for thirty years. While no footage of those descents appears to exist, this reel includes clips of Hollister walking underwater with a diving helmet and catching shallow water fish specimens.

After returning from her expeditions to Bermuda, Hollister would tour the United States on the lecture circuit, presenting her work at colleges, libraries, and women’s professional organizations. Her lectures were advertised as illustrating her deep-sea research work with colored lantern slides and films, shot with William Beebe in Bermuda. They could be edited in different versions—for a popular audience, a children’s audience, or a scientific one. Even after the advent of sound, these films were shown silently.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of the DTR Film Collection is its iterative nature. Its reels include different lecture versions; unlike Hollywood films, many of the DTR films are essentially variations on a theme, designed to be combined and recombined to suit various contexts.

Another valuable contribution of this collection is its emphasis on the daily working life of scientists. The films make a point of capturing how wildlife and natural history were being studied in the wild rather than through the examination of dead specimens. Beyond their potential impact on the scientific community of the day, the films were also posed to increase awareness about the practices of observation, exploration, and stewardship that wildlife research in the field enables.

According to Jayne Zanglein’s The Girl Explorers (2021), Hollister had met William Beebe when she was a college student and had seen his film “A Naturalist in the Guiana Jungle” as part of his 1923 lecture documenting the DTR’s field studies at “Kartabo” near the Mazaruni River in Guyana (then called British Guiana). Hollister was immediately enraptured by the glimpses these films provided into the life of researchers in tropical ecosystems. The impact that Beebe’s film had on Hollister’s own trajectory provides us with valuable insight into just how important the DTR films were in inspiring the imaginations of new generations of natural scientists.

Although the WCS Archives collection does not include “A Naturalist in the Guiana Jungle,” the film below contains footage from the DTR’s 1920s expeditions to Guyana.

In 1936, Gloria Hollister came full circle and made history by leading her own DTR expedition to Trinidad, Barbados, and the interior of Guyana. Taking a cue from her mentor William Beebe, Hollister brought the photographer Arthur Menken and the artist Ruth Walker Brooks to document the expedition. The WCS Archives includes films from this expedition that contain the field observations of the guacharo or oil-bird of Trinidad, the peculiar methods utilized in capturing flying fish, and the early life of the hoatzin. During part of the expedition Hollister and Menken were flown by Arthur Williams, an airplane pilot, and Harry Wendt, co-pilot, over Kaieteur Falls and Plateau. In the reel below is footage that was taken both from the ground and from those flights. During these flights, Hollister and Menken recorded 43 waterfalls that were new to Western records.

Jocelyn Crane joined the DTR staff in 1930, and for over 40 years she worked as a research zoologist alongside William Beebe. In 1952 she became the DTR’s assistant director, and after Beebe’s death in 1962 became the director. An expert on fiddler crabs, her fieldwork focused on studying the social behavior and evolution of crabs. For the majority of DTR films shot in the1940s through the 1960s Crane is credited as being behind the camera, filming wildlife in Venezuela, Bermuda, and Trinidad. The film below, “Biologist in the Tropics” (1954), skillfully illustrates the DTR’s approach to studying the behavior of tropical animals in the field.

In 1955, Jocelyn Crane was awarded a five-year grant from the National Science Foundation to further develop her body of research on crabs all over the world. Below is a travelogue-inspired film Crane made on her trip to Malaysia: “A Preface about William Beebe, and The Curious Crabs of Singapore” (1955). Narrated by Jocelyn Crane, the film documents her studies on 32 species of Ocypodid crabs. Her descriptions of various crabs, with focus on courtship behaviors, feeding, sheltering, and fighting, is interspersed with footage of Singapore waterfront and its bustling culture of canals.

Read more about the project on the WCS Newsroom.

This post was written by Leopold Krist, Project Archivist for the WCS Archives project Preserving Conservation Science and History: Digitizing the Department of Tropical Research Films. This project was supported by a Recordings at Risk grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR). The grant program is made possible by funding from the Mellon Foundation.