In the 1970s, the New York Zoological Society [NYZS] increased its efforts in international conservation, sponsoring external researchers and conservationists with projects that furthered the NYZS mission of protecting wildlife and wild places. NYZS-sponsored researchers conducted field work in countries far from home, often for several months at a time. Reporting back to the Society, they shared exciting scientific findings or provided updates on conservation efforts in regions including East Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia. But amid the progress reports and publications full of data from the field, the correspondence from field researchers gives a sense of the physical and logistical difficulties of conducting international research.

In the 1970s, the New York Zoological Society [NYZS] increased its efforts in international conservation, sponsoring external researchers and conservationists with projects that furthered the NYZS mission of protecting wildlife and wild places. NYZS-sponsored researchers conducted field work in countries far from home, often for several months at a time. Reporting back to the Society, they shared exciting scientific findings or provided updates on conservation efforts in regions including East Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia. But amid the progress reports and publications full of data from the field, the correspondence from field researchers gives a sense of the physical and logistical difficulties of conducting international research.

Often working in inhospitable climates (and sometimes in countries with inhospitable governments), field researchers pursued their work in sparse living conditions. John Terborgh, conducting a survey of birds and mammals near the Cocha Cashu Biological Station in Manu National Park, Peru, poetically described the isolated location:

“It is hard to convey a sense of the remoteness and isolation of Cocha Cashu. There are few places on earth so unsullied, so totally devoid of any sign of man, either present or past… [The one road out] provides a tenuous lifeline to the conveniences of the modern world – telephones, mail, hospitals and airplanes. In 1979 it was severed by landslides and washouts for five continuous months. Even when it is normally open, traffic can be blocked by mud or raging rivers, and in the best of times a truck may not venture into Shintuya for days on end… At Shintuya the river substitutes for the road as the only available channel of transport. Food, fuel, equipment and personnel must be transferred to dugout canoes… Two days of threading the log jams are required to reach our destination.” (John Terborgh, List of the birds and mammals found in the vicinity of Cocha Cashu Biological Station, Manu National Park, Peru, section 2: “The Study Site” )

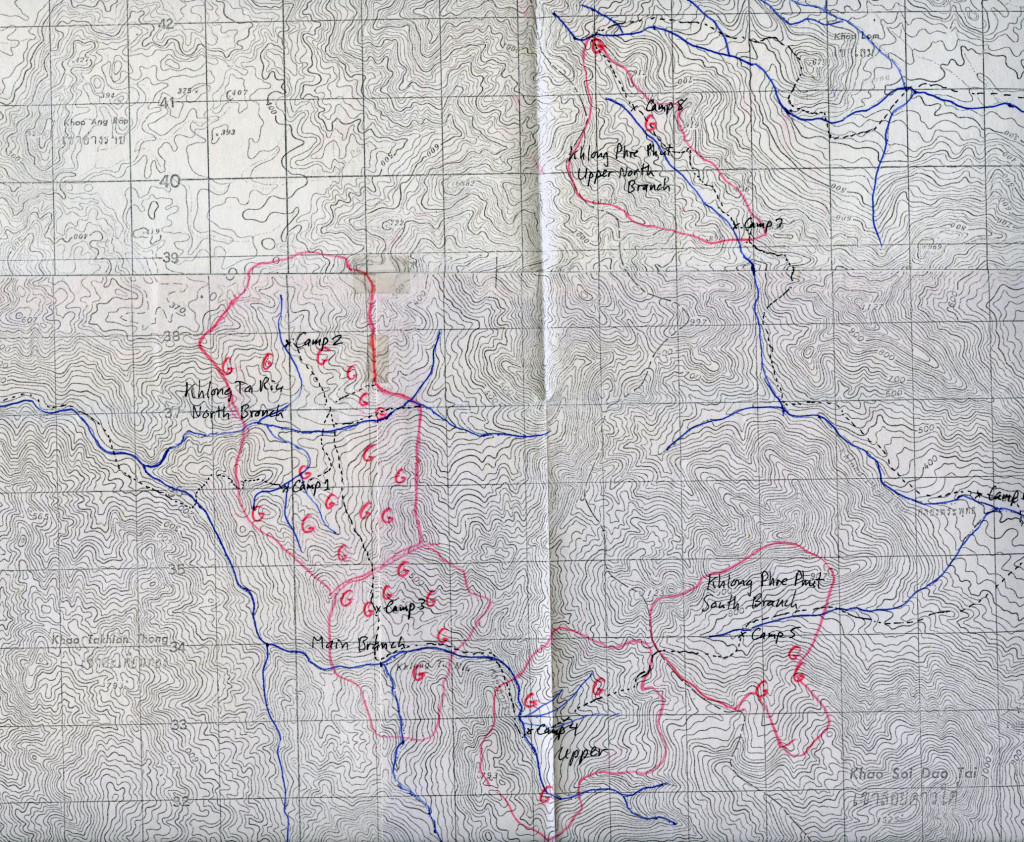

Warren Y. Brockelman’s annotated map of pileated gibbon research area in the Khao Soi Dao Wildlife Sanctuary, Chanthaburi, Thailand, 1977.

Though working relatively recently, field researchers in the 1970s and early 1980s had limited options for communication from these remote locations. Correspondence with NYZS officials often included laments about lost mail or apologies for long delays. For example, elephant ecology researcher James D. Allaway had to apologize to the Chair of the Society’s Conservation Department, F. Wayne King, for the delay in sending his six-month report: “I’m sorry not to have replied before now [July 6th] to your letter of March 19th, but I didn’t receive it until mid-June when I returned to Nairobi from the Tana.” Even primate researcher Jane Goodall, whose work with chimpanzees at Gombe Stream Research Center was funded by NYZS during the 1970s, lamented, “I feel a little frantic that half my letters never seem to arrive in America! Or else people’s replies never arrive in Tanzania!” (Jane Goodall to NYZS trustee Charles W. Nichols Jr., Oct 1st, 1978).

An airmail sent by researcher Derek Bryceson in Tanzania to NYZS General Director William Conway in November, 1976.

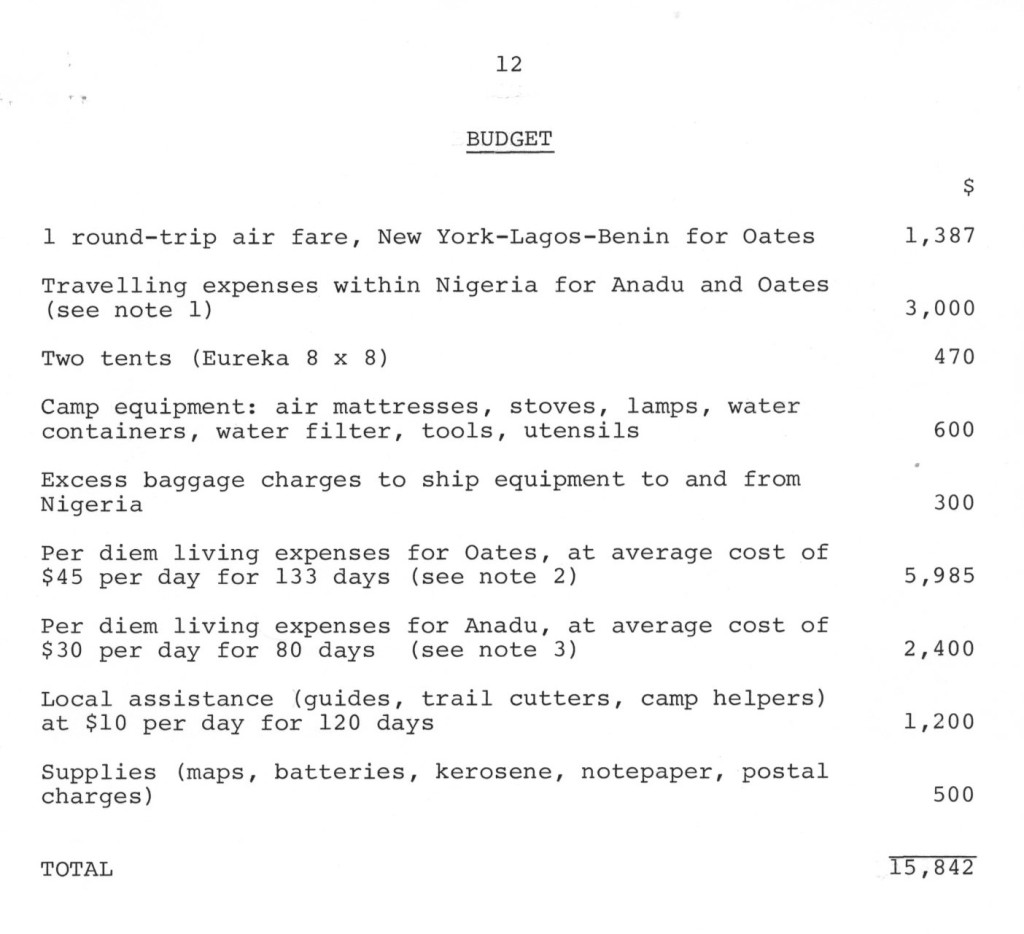

Isolated from colleagues and family in other continents, researchers also lived without many of the comforts of home. In a humorous but cautionary bulletin for his fellow field staff before an expedition to Belize, crocodile researcher C.L. Abercrombie advised, “I shan’t tell you what to take, but in general, if you think you need it, don’t bring it. If you know you need it, consider not bringing it” (undated, circa winter/spring 1984). Still, it is telling that Abercrombie did recommend bringing a “thick, slow-reading book” to pass the 7,000 mile journey via pickup truck. Grant applications to NYZS often included a list of supplies for the basic resources needed to set up a field camp:

Budget request by John Oates listing field supplies, in a project proposal to survey wildlife in Bendel State, Nigeria, July 1981.

Other issues were more serious. Extreme weather conditions or diseases such as malaria often threatened research projects and endangered staff. Political instability also posed a threat, as researchers dealt with local tensions, suspicions about foreign researchers, or precarious safety conditions. In a letter from March 3rd, 1978, Patsy M. Mink (who was then the Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs) explained to NYZS General Director William Conway that her Bureau could not fund Thomas Struhsaker’s scientific projects in Uganda at that time, with the US embassy closed due to the climate of “unsettled conditions” and threats against American residents. Although the US government was urging all American citizens to leave Uganda, Mink conceded that many were “reluctant to do so, for a variety of reasons including a sense of dedication to the worthwhile work being done by many of them in worthwhile fields.”

In 1981 the Society gave some of its trustees a chance to experience field conditions for themselves with an African safari trip to Sudan. Trustees, including Dr. Henry Clay Frick, Mr. and Mrs. John N. Irwin II, and John Pierrepont, made up the first group of tourists to visit the Boma Plateau in South Sudan, staying in a tented camp site that differed greatly from a modern U.S. home.

![A sketch conveying plans for the camp, included in a letter to trustees considering the trip, in 1980 [edit caption to account for Specific DATE].](http://www.wcsarchivesblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/4041-1980-Conway-trustee_expedition-1024x533.jpg)

A sketch conveying plans for the camp, included in a letter to trustees considering the trip, late 1980.

This post is by Alexanne Brown, who worked during Spring 2014 with the WCS Archives as an intern processing a collection of reports and correspondence pertaining to research projects funded by NYZS’s various international conservation departments and programs over the years. All items cited come from that collection: New York Zoological Society. International Conservation bluebooks, 1962-1993. Collection 4041.

![Boma Plateau camp dining tent with the table set for visiting NYZS trustees [edit caption to account for Specific DATE]](http://www.wcsarchivesblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/4041-1981-NYZS-trustee_expedition-02-1024x714.jpg)

A fascinating glimpse into the workings of this extraordinary organization and the people whose work has made it so successful. More, please?