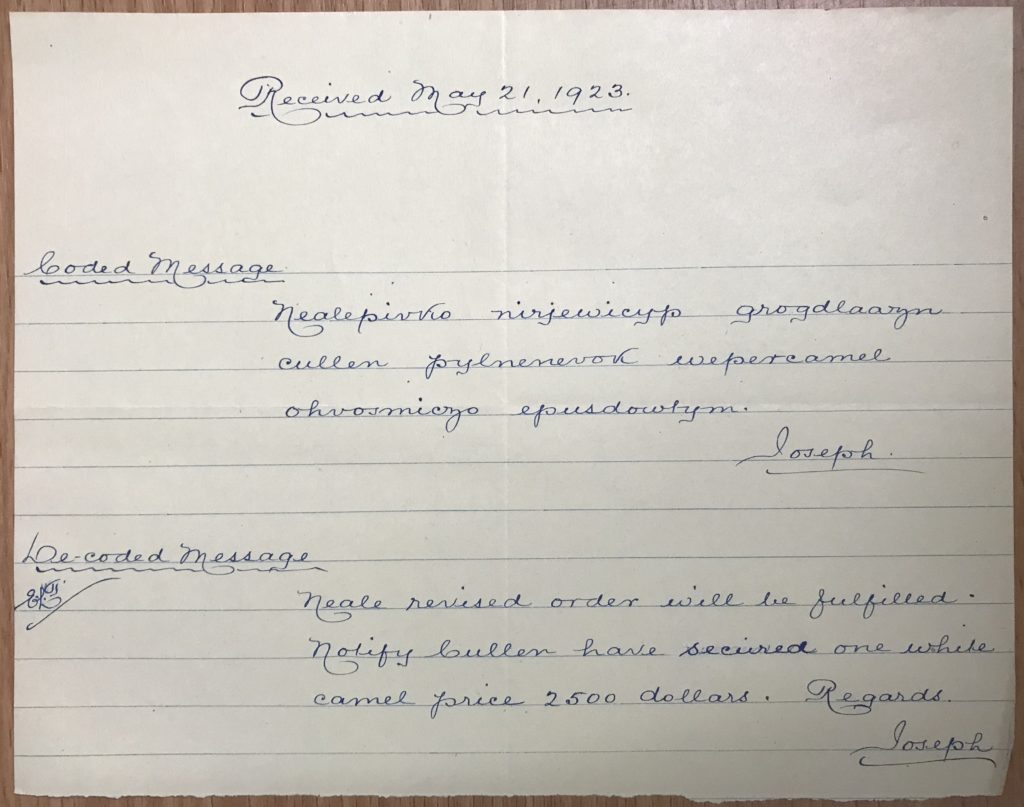

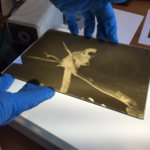

We are pleased to share the results of a Conservation Treatment Grant we received from the Greater Hudson Heritage Network. With this funding, we have been able to secure conservation treatment for a painting in our collection that holds historical, aesthetic, and cultural significance: Whooping Cranes on their Breeding Grounds in Saskatchewan, done in 1922 by the New York ornithologist and artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes and purchased from the artist in 1923 by the Wildlife Conservation Society for its artwork collection. Conservator Nadia Ghannam performed repairs, cleaning, and stabilization that has helped restore this painting’s vibrancy and ensure its longevity.

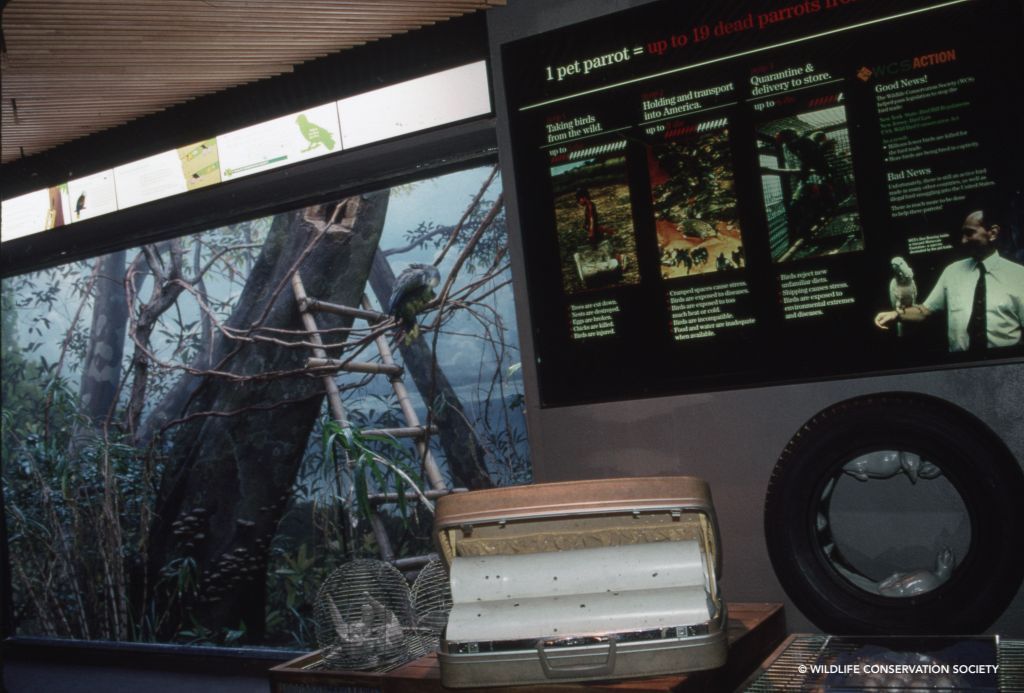

A lifelong New York resident who was considered the foremost American ornithological painter of his lifetime, Louis Agassiz Fuertes illustrated several of the era’s most important bird books, and he produced dozens of murals and oil paintings featuring birds in glorious detail. Fuertes’ particular significance, both to art history and ornithological history, was his approach to observing his subjects—an approach he honed alongside early WCS leaders. Like his associate, the Bronx Zoo’s first Curator of Birds, William Beebe, Fuertes was an early proponent of studying animals in their natural habitats. In this, they broke with researchers and artists before them, who had studied wildlife only from stuffed museum specimens. Instead, Fuertes and Beebe each traveled extensively to observe living birds. Among Fuertes’ expeditions, he visited Canada, where he performed intensive studies of the cranes he depicts so vividly in this painting. His first-hand observations of birds living in their natural habitats have been credited for the accuracy and vitality he brought to his ornithological paintings and showcased in these elegant and vivacious cranes. It is likewise significant that whooping cranes were among the birds central to one of the nascent wildlife conservation movement’s first public campaigns: to discourage the era’s destructive trend of using bird plumage to decorate women’s hats. Paintings like Fuertes’s illustrated the birds’ beauty in their natural settings and sought to inspire care for these threatened animals.

As described elsewhere on this blog, early WCS leaders saw art as a vital means of stimulating public interest in animals. Whooping cranes were of particular concern, and the Bronx Zoo’s first director feared that they would be “the next North American species to be totally exterminated.” Thankfully, that prediction has not borne out. While whooping cranes are still endangered, their numbers have risen since the early twentieth century, in part due to advocacy measures and captive breeding programs aided by many including WCS.

The NYSCA/GHHN Conservation Grant Treatment Program is made possible with public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, with support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature. The Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation has provided additional dedicated support for conservation treatment projects on Long Island and New York City.

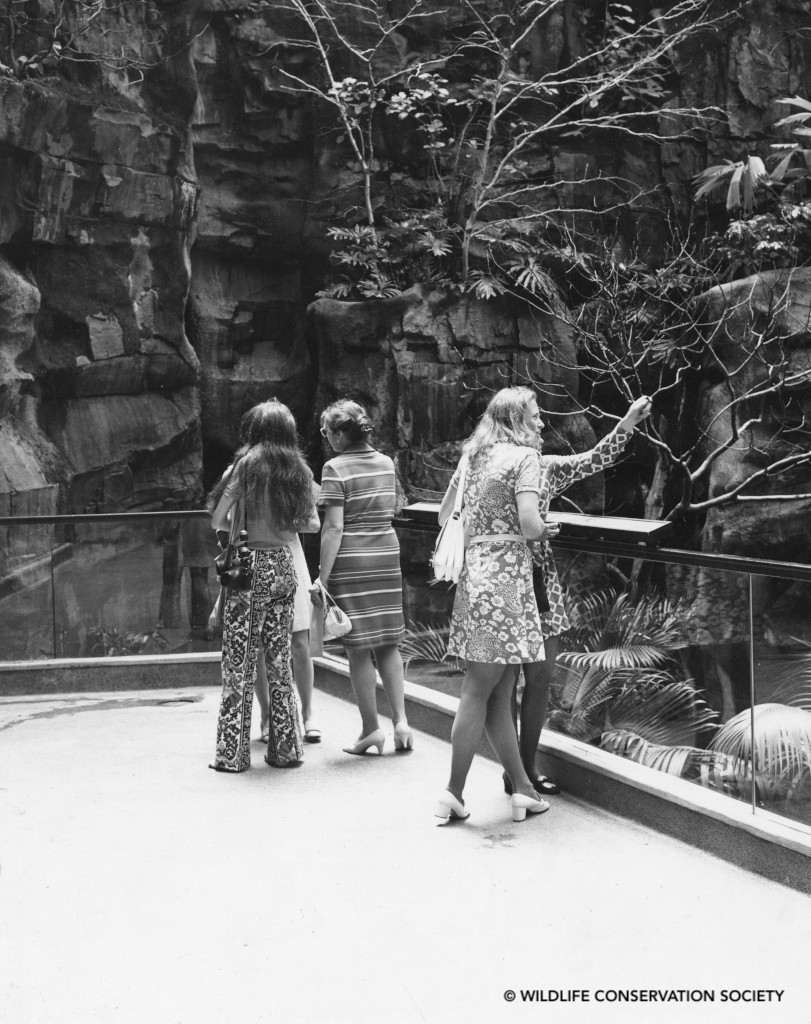

This Women’s History Month, we’re celebrating Grace Davall, who began her career in a secretarial role at the Bronx Zoo in 1923, at the age of 18, and rose through the ranks to become Assistant Curator of Mammals and Birds in 1952. Upon her retirement in 1970 until her death in 1985, she was designated Curator Emeritus.

This Women’s History Month, we’re celebrating Grace Davall, who began her career in a secretarial role at the Bronx Zoo in 1923, at the age of 18, and rose through the ranks to become Assistant Curator of Mammals and Birds in 1952. Upon her retirement in 1970 until her death in 1985, she was designated Curator Emeritus.