This post was written by Kimio Honda, Studio Manager in WCS’s Exhibition and Graphic Arts Department.

This post was written by Kimio Honda, Studio Manager in WCS’s Exhibition and Graphic Arts Department.

My interest in the Bronx Zoo and the New York Zoological Society goes back to my teenage years in Japan. When I was transferred to New York for my work, I got to know some people at the zoo. Many years later I started working at the Exhibition and Graphic Arts Department (known around here as EGAD). As a result, I have had a chance to know more intimately the works of art around our parks and to hear some interesting stories.

So I have offered to write some pieces for the WCS Archives Blog about some public art pieces at the Bronx Zoo, and possibly other WCS parks, along with interesting stories associated with them. Since I am not an art expert, this is by no means a definitive guide. Rather, my hope is that these pieces will help others notice these works of art and may even lead to deeper studies.

As the first entry I have chosen the Rainey Memorial Gates. To those of us who know the magnificent gateway of bronze sculptures, it is the icon of the Bronx Zoo. But I think many visitors and even some staff members might not notice it.

The Rainey Gates at the Bronx Zoo. Kimio Honda © WCS

The Rainey Gates, as we usually call them, stand at the entryway known as Fordham Road Gate on Fordham Road, facing north toward the New York Botanical Garden. The gateway was presented to the New York Zoological Society as a memorial to Paul J. Rainey, a big game hunter, by his sister Mrs. Grace Rainey Rogers. She commissioned the sculptor Paul Manship to create it. The gateway was opened for use on May 10, 1934, at the annual garden party of the Society, but according to a press release held in the WCS Archives, the official ceremony of dedication was held on June 14 since Mrs. Rogers was unable to attend the garden party.

Dedication to Paul J. Rainey. Kimio Honda © WCS

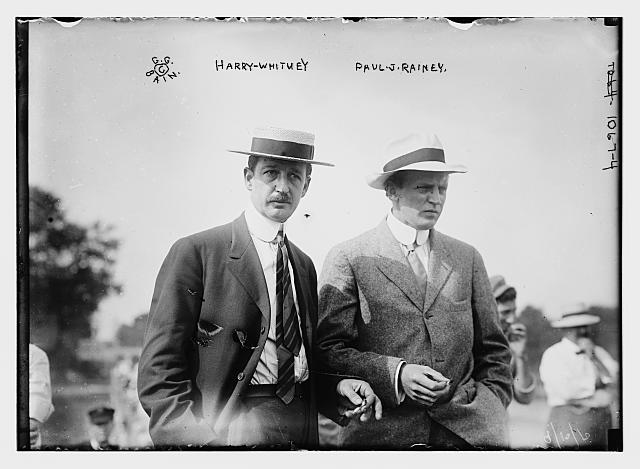

Paul James Rainey (1877–1923) was an adventurer, sportsman, and playboy who inherited a fortune from his family’s coal and coke business in Cleveland. In 1910, Rainey and his friend Harry Whitney chartered a steamer and sailed for the Arctic, returning some months later with a collection of native animals.

This collection included the famed polar bear Silver King, captured as a full-grown male using nothing but ropes and reckless adventurer spirit. Rainey contributed a story of the capture in the January 1911 issue of the Zoological Society Bulletin. It reads almost like a script of a monster movie and could make some readers of today uncomfortable. The aforementioned press release for the dedication of the gateway, written by Curator of Publications William Bridges, mentions a female polar bear known as Silver Queen, six musk oxen, and a walrus as other gifts from Rainey to the Society.

Whitney and Rainey, September 10, 1910. Image from original Bain News Service negative held by the Library of Congress.

Rainey had a series of hunting trips to Africa as well, and in 1923 as he sailed from Southampton to Cape Town for another safari, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage. It was his forty-sixth birthday. Aside from the live animals, Rainey presented many specimens to museums, and after Rainey’s death, some of his trophies were given to the Heads and Horns Museum, formerly located at the Bronx Zoo.

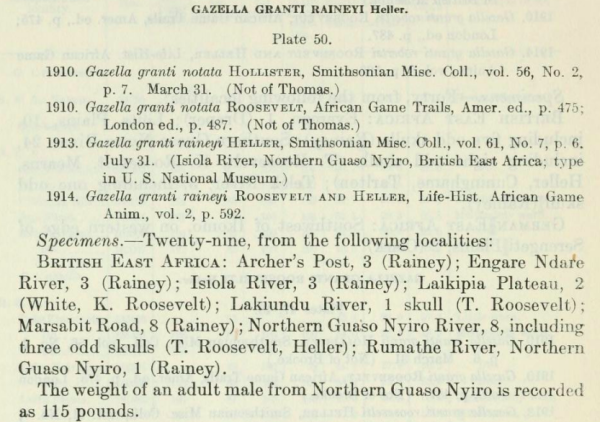

The Life Nature Library used to be an invaluable source of photographs and illustrations of wildlife. It was already somewhat aged when I came to know it, but I treasured “Africa” in the series in particular. It had a spread featuring beautiful pen and ink drawings of nearly 30 antelope heads, and among them was “Rainey’s Gazelle.” This subspecies of Grant’s Gazelle surely must have been named after Paul J. Rainey, based on the specimens brought back by himself as well as Theodore Roosevelt. (See the US National Museum Bulletin 99, East African Mammals in the United States National Museum, p. 122.) Today it is no longer considered a valid subspecies.

Description of Gazella granti raineyi from US National Museum Bulletin 99, East African Mammals in the United States National Museum

Among today’s readers there might be some who raise their eyebrows at a big game hunter being the zoo’s benefactor. But those were the days, and the responsible hunters were among the first to notice the decline of wildlife and needs for its conservation. WCS owes its founding to the Boone and Crockett Club, and even today responsible hunters can be important conservation allies. Paul Rainey’s conservation legacy includes a 26,000-acre marshland in Louisiana, the Paul J. Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary, set up after his death by his family and now owned by the National Audubon Society.

More on the history of the gates to follow in the next Wild Things post.

Pingback: Cope Lake, Bronx Zoo – Hidden Waters blog