Few things can compare to the thrill of seeing a whale at sea. Every year, thousands of nature enthusiasts head out to sea in search of these leviathans, which to many have become the embodiment of nature itself. What’s the attraction? Whales are gigantic and graceful animals exquisitely adapted to the marine environment, and—as we have come to learn over the past half century—behaviorally sophisticated and intelligent. As mammals that left the land more than 50 million years ago, they are distant relatives after all, alien yet somehow familiar and endearing.

Few things can compare to the thrill of seeing a whale at sea. Every year, thousands of nature enthusiasts head out to sea in search of these leviathans, which to many have become the embodiment of nature itself. What’s the attraction? Whales are gigantic and graceful animals exquisitely adapted to the marine environment, and—as we have come to learn over the past half century—behaviorally sophisticated and intelligent. As mammals that left the land more than 50 million years ago, they are distant relatives after all, alien yet somehow familiar and endearing.

Humpback whale, Antongil Bay, Madagascar, 2004. WCS Photo Collection. Photo by Julie Larsen Maher © WCS.

Perhaps the star of the great whales is the humpback whale, a standout performer among the many species of the world. Much of what they do appears thrilling to observers. The humpback often slaps the surface of the water with its tail and elongated pectoral fins. Groups of humpbacks feeding on herring, sand lance, and other small fish create monumental spectacles with the marine mammals erupting on the surface in an effort to engulf entire schools of fish. And they regularly throw their entire bodies out of the water in an activity called breaching. Of course, other whales do these things, but not with the panache of the humpback whale.

The humpback whale possesses another talent, that—when originally discovered—helped change public attitudes of whales at a time when the world’s whale populations were being wiped out by commercial whaling fleets. In 1970, the songs of humpback whales were introduced to large swaths of society, the profound impact upon whom gave conservationists a powerful tool in the fight to save whales.

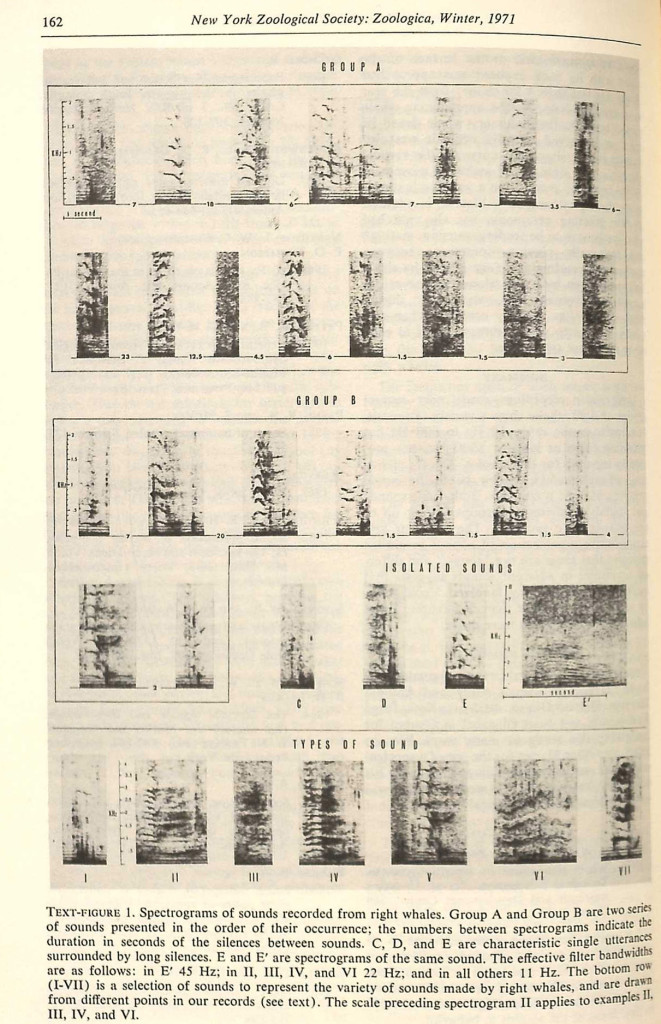

For much of the twentieth century, scientists had known that whales “vocalize.” One of the first recordings of humpback whale sounds was made by Frank Watlington, a sound pioneer working at the SOFAR station on the island of Bermuda in the early 1960s. While listening for Soviet submarines and other underwater sounds, he captured long recordings of humpback whales using a hydrophone array built for national defence. An analysis of the recordings made by former New York Zoological Society researcher Roger Payne and Scott McVay of Princeton University revealed something noteworthy in the late 1960s: humpback whales sing long complicated songs—full of eerie calls, grunts, and rumbles—they repeat once completed, often without a pause. The authors knew the discovery was significant, particularly since many whale species had been hunted to the brink of extinction by the world’s commercial whaling fleets. Perhaps the songs themselves could become tools to bring about reform.

Spectograms of sounds recorded from right whales. From Roger Payne and Katherine Payne, Underwater sounds of southern right whales. Zoologica 56.7 (1971): 162.

The decision to release Songs of the Humpback Whale as a popular album was made by Payne and former NYZS Director William Conway, both of whom realized the recordings of whales themselves might help build support for whale conservation. To that end, NYZS released Songs of the Humpback Whale, a vinyl introduction to the world of whale songs that appeared even before the peer-reviewed study in the journal Science became available in 1971.

Upon its initial release, Songs of the Humpback Whale sold at a brisk pace as the public embraced the LP album containing something new: songs assembled by non-human composers emanating from the deep. In 1971, the album would make the Billboard 200 charts and stay there for eight weeks, peaking at 176. The record would go on to become the best selling natural history record of all time.

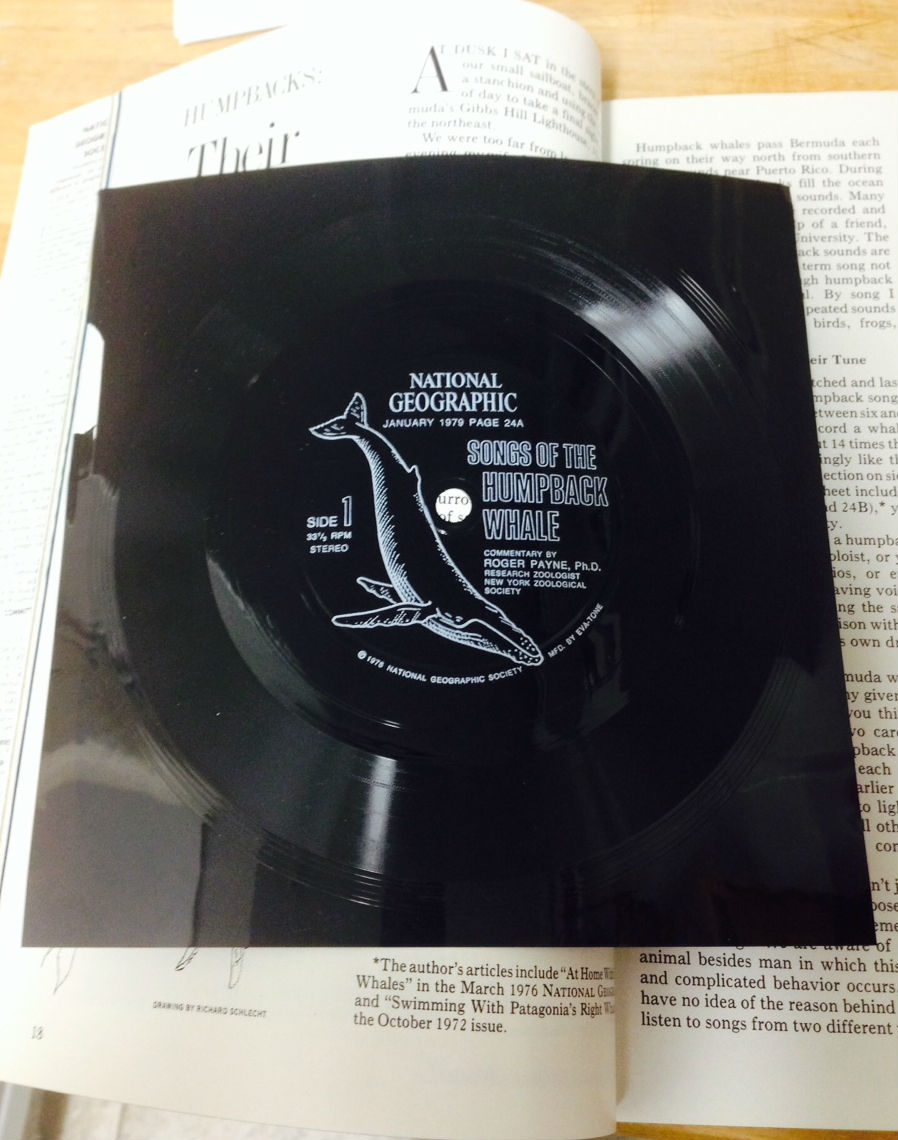

At the same time, Payne and co-author Scott McVay toured the interview circuit in an effort to spread the word about the extraordinary singing talents of whales and the fact that these great mammals were being hunted to extinction. In 1979, Payne and other conservationists received a massive boost from the National Geographic Society, which printed 10.5 million shortened copies of Songs of the Humpback Whale for insertion in its magazine, bringing the sounds of whales into literally millions of homes worldwide. The pressing of the small flexible record insert was the largest press run of any recording at that time.

Worth noting is the enormous effect the recordings had on popular musicians in the early 1970s. The list of recording artists who either used the recordings directly in their own songs or at least drew inspiration from them was a long one, including Joan Collins; Crosby, Stills, and Nash; Alan Hovhaness; Paul Winter; and many others. Many music fans in turn became conservationists and lent their support to myriad environmental causes.

In addition to the record-buying public, many of the US’s leading scientists fell under the spell of the haunting wails and moans of the humpback whale. Planners of the Voyager space missions to the outer planets—particularly Carl Sagan of Cosmos fame—earmarked tracks from Songs of the Humpback Whale for inclusion on a gold record containing greetings in 55 languages, images, and music. The record was mounted on the Voyager spacecraft, which is now billions of miles from Earth. Perhaps one day an alien species may hear the sounds of Earth, including the songs of whales.

“The Sounds of Earth – GPN-2000-001976” by NASA. Image licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Songs of the Humpback Whale also helped pave the way for real conservation victories. Activists used the recordings to help secure lasting protective measures for the world’s whale populations. Roger Payne and Scott McVay themselves played the recordings to everyone who would listen, including elected officials on Congressional subcommittees and the Department of Interior. Humpback whale songs certainly had an influence on supporters of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which was passed in 1972, and the inclusion of great whale species in the Endangered Species Act the following year. Humpback whale songs provided the “Save the Whales” movement with an invaluable PR tool. The biggest victory for anti-whaling advocates came in 1986, the year the international moratorium on commercial whaling went into effect.

The Whale Fund Manual, 1971. WCS Archives Collection 2016. The New York Zoological Society began the whale fund to provide resources for the study and conservation of endangered whales.

The commercial whaling moratorium still remains in effect, but whales still face a number of indirect human-related threats. Coastal development, pollution, and anthropogenic noise from shipping and other activities still pose a risk. On the other hand, whale songs are so familiar to the public that they have become cultural memes, known to millions of people through the original recordings of Songs of the Humpback Whale as well as popular movies such as Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home and Finding Nemo. The reverberations of Songs of the Humpback Whale can still be heard in the world’s media and the continuing battle to protect the world’s whales.

This post is by John Delaney, Assistant Director of Communications at WCS. Click here to learn more about WCS’s ongoing work with humpback whales and other ocean giants. And see John’s related piece on WCS’s photo blog, Wild View.