At the Bronx Zoo the approach of Spring brings warmer weather, and thus increasing crowds enjoying the park. As the season progresses the Horticulture, Maintenance, and Operations Departments, as well as various others, all find themselves increasingly busy with the work of keeping the Zoo presentable. A century ago these departments’ predecessors also joined the fight to maintain the grounds. During the early 20th Century, however, Director William Hornaday, treating the efforts to keep the Zoo clean like one of his conservation campaigns, gave what he called ‘The Rubbish War’ a hyperbolic air not seen in today’s spring cleanings.

At the Bronx Zoo the approach of Spring brings warmer weather, and thus increasing crowds enjoying the park. As the season progresses the Horticulture, Maintenance, and Operations Departments, as well as various others, all find themselves increasingly busy with the work of keeping the Zoo presentable. A century ago these departments’ predecessors also joined the fight to maintain the grounds. During the early 20th Century, however, Director William Hornaday, treating the efforts to keep the Zoo clean like one of his conservation campaigns, gave what he called ‘The Rubbish War’ a hyperbolic air not seen in today’s spring cleanings.

As early as 1906, Hornaday lamented that around two-thirds of the Zoo’s employees were involved in “keeping the whole Zoological Park in clean and acceptable condition” (NYZS 1906 Annual Report, page 72). Former New York Zoological Society [NYZS] Curator of Publications, William Bridges, explained in his history of NYZS how Hornaday designed a new rubbish basket specifically for the Zoo:

In 1907, Hornaday had 100 of these new baskets deployed around the park. The ‘War’ officially started the year after, in May 1908, with 150 large anti-littering signs displayed in prominent zoo locations and a “a manifesto by the Director [that] appeared in several of the newspapers of New York City, formally declaring war on the rubbish-throwing habit” (Hornaday, writing about himself in the third person in the New York Zoological Society Bulletin, October 1908, pages 456-457).

Hornaday celebrated the results of that first campaign by noting the encouragements his efforts had received; he followed up with exhortations to the people and officials of the City to continue the work [ibid.]. However, this work would prove to be an ongoing project: Hornaday would find himself continuing his struggle against litter for the next 15 years, taking his fight from the grounds of the Zoological Park to New York City’s Mayors—particularly John P. Mitchel —Police Commissioners, and Parks Commissioners.

In the first few years following 1908, the Rubbish War saw mixed success; already by early 1910, when writing the 1909 Annual Report, Hornaday started expressing worries that his zeal would need to be sustained over a long term:

A great deal of time was devoted to the crusade against the indiscriminate throwing about of refuse […]. From fifteen to eighteen men were employed on this work every Sunday, […] and with marked effect. That this crusade, however, will have to be one of continued effort, was clearly shown by the one or two Sundays on which the force was reduced. (NYZS 1909 Annual Report, page 76)

Hornaday’s incoming and outgoing letters on the subject show that he received sympathy and encouragement, but little concrete success.

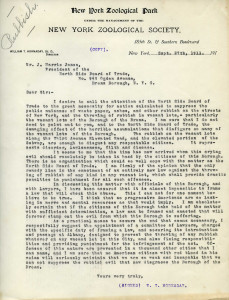

From WCS Archives Hornaday-Blair Correspondence Collection 1001, Hornaday to the North Side Board of Trade, September 1911. A same-day response from the Board of Trade is linked to (in pdf form) above.

Meanwhile, rubbish remained on the grounds …

… and Hornaday continued to rail against its presence, the people who left it, and the City’s police force for not doing much about it:

Thumbnails: Links to updates on the Rubbish War from the 1911 Bulletin and 1912 and 1914 Annual Reports.]

Thumbnails: Links to updates on the Rubbish War from the 1911 Bulletin and 1912 and 1914 Annual Reports.]

In fact, Hornaday’s vitriolic exhortations, while continuing over the next few years, didn’t gain results until 1915, when the first-term reform Mayor, John P. Mitchel, lent his support to Hornaday’s campaign. In the 1915 Annual Report, Hornaday had nothing but praise for Mitchel, his Police Commissioner, Arthur Woods, and the rest of the new administration:

The incoming of Mayor Mitchel was regarded as an opportunity to carry into effect a sweeping reform. When the situation had been fully put before him he decided to take the initiative, and set in motion the machinery that would yield clean parks for Greater New York. […]

Up to April 30 the vandals were in the saddle. The sneaks who sit on comfortable benches and slyly throw rubbish under or behind them, were enjoying life to the utmost. The thousands of sneaks who slyly strew peanut shells on the walks and grass borders were buying peanuts with great diligence, and the nine peanut stands near the three busy entrances of the Zoological Park were doing a thriving trade. Every Monday morning the peanut shells and waste paper in the Zoological Park was a sickening sight, and there were other parks which we will not name which were quite as badly disfigured. […]

To-day the cleanliness of our walks and walk borders is a constant joy. One can walk through our grounds without feelings of rage and mortification. We owe all this new condition to Mayor Mitchel, Police Commissioner Wood [sic], and the City Magistrates, particularly Judges McAdoo, Crane, House and Cornell. (NYZS 1915 Annual Report, pages 63-65)

Hornaday’s success lasted throughout Mitchel’s term; indeed in 1916 the anti-littering code Hornaday had insisted upon for the Zoo was put into effect at all New York City parks (NYZS 1916 Annual Report, pages 65-66).

After Mitchel was succeeded by John F. Hylan, however, Hornaday’s efforts saw diminishing returns. The 1917 and 1918 Annual Reports mention arrests and summonses that were issued for violations of the anti-litter ordinance, but Hornaday’s lobbying had considerably less effect on Hylan and his new Police Commissioner, Richard Enright, than they had on Mitchel and Woods.

WCS Archives. Hornaday-Blair Collection 1001. Hornaday to Police Commissioner Enright, June 1918

Hornaday had somewhat better luck with Joseph Hennessy, the Bronx Parks Commissioner, who was the first to call for a special NYPD detail devoted to city parks. However, even while lauding Hennessy, Hornaday sounded as if he had grown tired of repeating himself, calling “the tendency toward vandalism in public parks […] too well known to require description” (1919 Annual Report, page 105).

Hennessy, however, urged Hornaday to continue speaking his mind:

Nevertheless, the efforts didn’t continue much longer, as Hornaday retired from the Bronx Zoo in 1926.

These days at the Zoo, it’s rare to see peanut shells, newspapers, bottles, and other debris in quite the profusion that Hornaday railed against. Parks Commissioner Hennessy’s NYPD Parks detail has had a long-time presence on the grounds, and zoo-goers have had decades to get accustomed to (generally) not littering in parks. And for those who still do, we have our ever-vigilant facilities departments on hand to continue Hornaday’s ‘Rubbish War’!

Three cheers and many thanks to the cheerful and effective men and women who keep BZ clean these days. It must be the cleanest place in the city, even on our busiest days. Not an easy thing to accomplish!